|

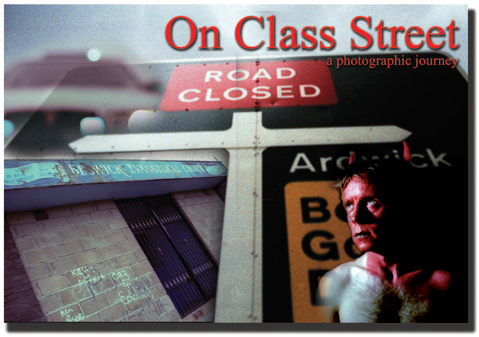

On Class Street |

||||||

|

|

||||||

The

book documents, creatively, what it was like growing up, living and

working on an extremely large council estate called Beswick, in inner

city Manchester during the eighties. It is ironic that one of the main

areas of employment for local working class people (a large industrial

estate) was called Class Street. This book takes the reader on a journey

through one of the most dramatic periods of social change that

Manchester has ever seen. The area of Beswick suffered extreme high

unemployment, and just as badly from the negative stereotyping of its

inhabitants. Parts of the book successfully counter these negative

stereotypes. Beswick is an area that is representative of many other

council estates across the United Kingdom.

The

book documents, creatively, what it was like growing up, living and

working on an extremely large council estate called Beswick, in inner

city Manchester during the eighties. It is ironic that one of the main

areas of employment for local working class people (a large industrial

estate) was called Class Street. This book takes the reader on a journey

through one of the most dramatic periods of social change that

Manchester has ever seen. The area of Beswick suffered extreme high

unemployment, and just as badly from the negative stereotyping of its

inhabitants. Parts of the book successfully counter these negative

stereotypes. Beswick is an area that is representative of many other

council estates across the United Kingdom.

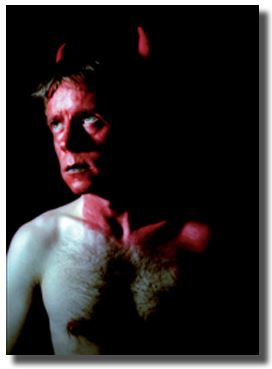

deviant, and this is before anybody has spoken to him, let alone knows

him. I have used a quote from the theoretician

and psychologist, Winnicott. It is next to the photo-montage at the top

of this page (when I look, I am seen so

I exist...), it is also used in my book, on page 70. This particular

quote concerns mirroring and the gaze of the mother. Winnicott's (and

others) concept of mirror reactions is also about the infant 'gaining'

an 'identity' through the mothers gaze. My use of Winnicott's idea has

been put to use in a metaphorical sense. The infant (me) and important

role models from within my local environment (surrogate mother). The

quotation is juxtaposed next to

an image of me in which I have undergone a psychological transformation,

taking on an unreal identity (phantasy). This is how I was made to feel

when I was a child, a part of my (and others) fragmented identity. Once

an identity has been found, this identity 'exists'. This identity, or

this 'other self', was not 'created' by me alone. Rather, I had

internalized and synthesized the 'gaze' of various institutional figures

from religion, law, and education during the course of my childhood

development. It was how I perceived that I was being perceived by

certain figures that played important roles in my life. The image

reflected in the mirror is not entirely my own, but the complex gaze of

the 'surrogate' mother.

deviant, and this is before anybody has spoken to him, let alone knows

him. I have used a quote from the theoretician

and psychologist, Winnicott. It is next to the photo-montage at the top

of this page (when I look, I am seen so

I exist...), it is also used in my book, on page 70. This particular

quote concerns mirroring and the gaze of the mother. Winnicott's (and

others) concept of mirror reactions is also about the infant 'gaining'

an 'identity' through the mothers gaze. My use of Winnicott's idea has

been put to use in a metaphorical sense. The infant (me) and important

role models from within my local environment (surrogate mother). The

quotation is juxtaposed next to

an image of me in which I have undergone a psychological transformation,

taking on an unreal identity (phantasy). This is how I was made to feel

when I was a child, a part of my (and others) fragmented identity. Once

an identity has been found, this identity 'exists'. This identity, or

this 'other self', was not 'created' by me alone. Rather, I had

internalized and synthesized the 'gaze' of various institutional figures

from religion, law, and education during the course of my childhood

development. It was how I perceived that I was being perceived by

certain figures that played important roles in my life. The image

reflected in the mirror is not entirely my own, but the complex gaze of

the 'surrogate' mother.